First, a preliminary look at trees. (This should be review. Some of this material is taken from Thomas Standish Data Structure Techniques (1980) and Goodrich & Tamassia (1998) as well as the Cormen appendix, but is widely published.)

If G=(V, E) is a finite graph with v > 1 vertices, the following properties are equivalent definitions of a generalized or free tree:

Each of these is a proposed definition of free trees. The Fundamental Theorem states that these definitions are equivalent. A classic exercise in basic graph theory is to prove each of these statements using the one before it, and #1 from #6.

When we use the term "tree" without qualification, we will assume that we mean a free tree unless the context makes it clear otherwise (e.g., when we are discussing binary trees).

In some contexts, G=({}, {}) and G=({v}, {}) are also treated as trees. These are obvious base cases for recursive algorithms.

A forest is a (possibly disconnected) graph, each of whose connected components is a tree.

An oriented tree is a directed graph having a designated vertex r, called the root, and having exacly one oriented path between the root and any vertex v distinct from the root, in which r is the origin of the path and v the terminus.

In some fields (such as social network analysis), the word "node" is used interchangeably with "vertex". I use "vertex" in these notes but may slip into "node" in my recorded lectures or in class.

A binary tree is a finite set of vertices that is either empty or consists of a vertex called the root, together with two binary subtrees that are disjoint from each other and from the root and are called the left and right subtrees. Binary trees are ubiquitous in computer science, and you should understand their properties well.

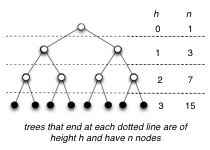

A full binary tree is a binary tree in which each vertex either is a leaf or has exactly two nonempty descendants. In a full binary tree of height h:

A complete binary tree is full binary tree in which all leaves have the same depth and all internal vertices have degree 2 (e.g., second example figure).

(Note: some earlier texts allow the last level of a "complete" tree to be incomplete! They are defined as binary trees with leaves on at most two adjacent levels l-1 and l and in which the leaves at the bottommost level l lie in the leftmost positions of l.)

A binary search tree (BST) is a binary tree that satisfies the binary search tree property:

BSTs provide a useful implementation of the Dynamic Set ADT, as they potentially support most of the operations efficiently (with exceptions we will discuss and deal with).

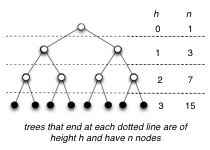

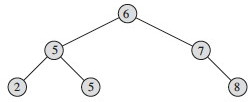

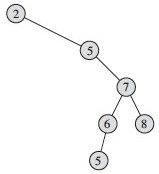

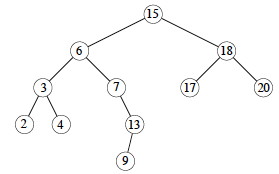

Two examples on the same data:

As an alternative definition, why don't we just say "if y is the left child of x then y.key ≤ x.key, and "if y is the right child of x then y.key ≥ x.key,, and rely on transitivity? What would go wrong?

Implementations of BSTs include a root instance variable. Implementations of BST vertices usually include fields for the key, left and right children, and the parent.

Note that all of the algorithms described here are given a tree vertex as a starting point. Thus, they can be applied to any subtree of the tree as well as the full tree.

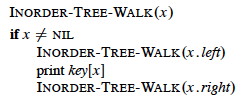

Traversals of the tree "visit" (e.g., print or otherwise operate on) each vertex of the tree exactly once, in some systematic order. This order can be Inorder, Preorder, or Postorder, according to when a vertex is visited relative to its children. Here is the code for inorder:

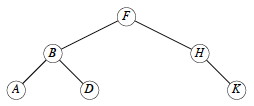

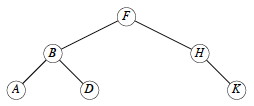

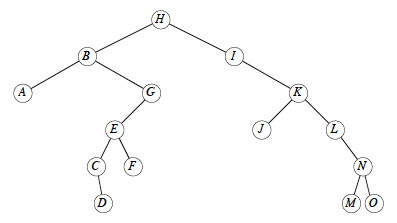

Quick exercise: Do INORDER-TREE-WALK on this tree ... in what order are the keys printed?

Quick exercise: How would you define Preorder traversal? Postorder traversal?

Traversals can be done on any tree, not just binary search trees. For example, traversal of an expression tree will produce preorder, inorder or postorder versions of the expressions.

Time: Traversals (INORDER-TREE-WALK and its preorder and postorder variations) take T(n) = Θ(n) time for a tree with n vertices, because we visit and print each vertex once, with constant cost associated with moving between vertices and printing them. More formally, we can prove as follows:

T(n) = Ω(n) since these traversals must visit all n vertices of the tree.

T(n) = O(n) can be shown by substitution. First the base case of the recurrence relation captures the work done for the test x ≠ NIL:

T(0) = c for some constant c > 0

To obtain the recurrence relation for n > 0, suppose the traversal is called on a vertex x with k vertices in the left subtree and n−k−1 vertices in the right subtree, and that it takes constant time d > 0 to execute the body of the traversal exclusive of recursive calls. Then the time is bounded by

T(n) ≤ T(k) + T(n−k−1) + d.

We now need to "guess" the inductive hypothesis to prove. The "guess" that CLRS use is T(n) ≤ (c + d)n + c, which is clearly O(n).

How did they get this guess? As discussed in Chapter 4, section 4 (especially subsection "Subtleties" page 85-86), one must prove the exact form of the inductive hypothesis, and sometimes you can get a better guess by observing how your original attempt at the proof fails, and then making an adjustment with an additional constant d as a factor or term. This is likely what CLRS did.

We'll go directly to proving their hypothesis by substitution (showing two steps skipped over in the book):

Inductive hypothesis: Suppose that T(m) ≤ (c + d)m + c for all m < n

Base Case: (c + d)0 + c = c = T(0) as defined above.

Inductive Proof:

T(n) ≤ T(k) + T(n−k−1) + d by definition

= ((c + d)k + c) + ((c + d)(n−k−1) + c) + d substiting inductive hypothesis for values < n

= ((c + d)(k + n − k − 1) + c + c + d collecting factors

= ((c + d)(n − 1) + c + c + d simplifying

= ((c + d)n + c − (c + d) + c + d multiplying out n−1 and rearranging

= ((c + d)n + c. the last terms cancel.

We showed that if we assume the hypothesis for smaller values then it is true for larger values; and we also showed it for the smallest value, so the 'dominos' all fall..

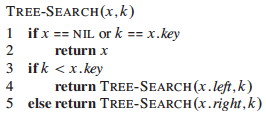

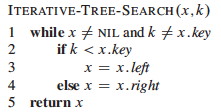

Here are two implementations of the dynamic set operation search:

Quick exercise: Do TREE-SEARCH for D and C on this tree ...

For now, we will characterize the run time of the remaining algorithms in terms of h, the height of the tree. Then we will consider what h can be as a function of n, the number of vertices in the tree.

Time: Both of the algorithms visit vertices on a downwards path from the root to the vertex sought. In the worst case, the leaf with the longest path from the root is reached, examining h+1 vertices (h is the height of the tree, so traversing the longest path must traverse h edges, and h edges connect h+1 vertices).

Comparisons and movements to the chosen child vertex are O(1), so the algorithm is O(h). (Why don't we say Θ?)

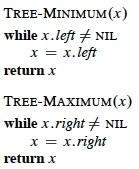

The BST property guarantees that:

(Why?) This leads to simple implementations:

Time: Both procedures visit vertices on a path from the root to a leaf. Visits are O(1), so again this algorithm is O(h).

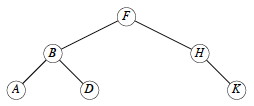

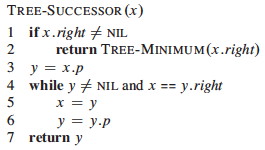

Assuming that all keys are distinct, the successor of a vertex x is the vertex y such that y.key is the smallest key > x.key. If x has the largest key in the BST, we define the successor to be NIL.

We can find x's successor based entirely on the tree structure (no key comparison is needed). There are two cases:

It's worth diagramming the second case on paper to make sure you understand the reasoning. Then apply the following algorithm to that diagram.

Exercise: Write the pseudocode for TREE-PREDECESSOR

Now trace the operations: Tree-Minimum and Tree-Maximum starting at the root; Tree-Successor starting at 15, 6, 4 and 13; and Tree-Predecessor starting at 6 and 17:

Time: The algorithms visit notes on a path down or up the tree, with O(1) operations at each visit and a maximum of h+1 visitations. Thus these algorithms are also O(h). (We will define h in terms of n after all operations are introduced.)

Exercise: Show that if a vertex in a BST has two children, then its succesor has no left child and its predecessor has no right child.

The BST property must be sustained under modifications. This is more straightforward with insertion (as we can add a vertex at a leaf position) than with deletion (where an internal vertex may be deleted).

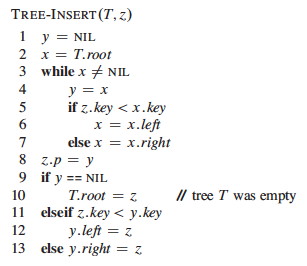

The algorithm assumes that the vertex z to be inserted has been initialized with z.key = v and z.left = z.right = NIL.

The strategy is to conduct a search (as in tree search) with pointer x, but to sustain a trailing pointer y to keep track of the parent of x. When x drops off the bottom of the tree (becomes NIL), it will be appropriate to insert z as a child of y.

Comment on variable naming: I would have preferred that they call x something like leading and y trailing.

Try TREE-INSERT(T,C):

Time: The same as TREE-SEARCH, as there are just a few additional lines of O(1) pointer manipulation at the end.

How could you use TREE-INSERT and INORDER-TREE-WALK to sort a set of

numbers?

How would you prove the time complexity of the resulting

algorithm?

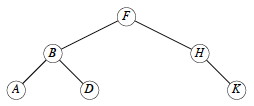

Deletion is more complex, as the vertex z to be deleted may or may not have children. We can think of this in terms of three cases:

Exercise: diagram trees on paper to see why these manipulations make sense, especially the third case!

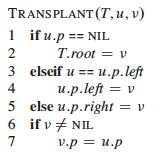

The code organizes the cases differently to simplify testing and make use of a common procedure for moving subtrees around. This procedure replaces the subtree rooted at u with the subtree rooted at v.

It is worth taking the time to draw a few examples.

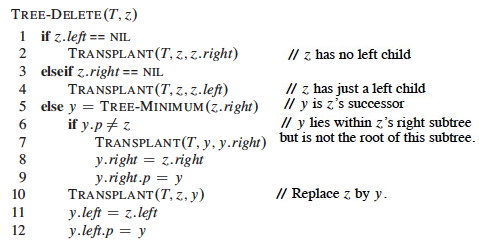

Here are the four actual cases used in the main algorithm TREE-DELETE(T,z):

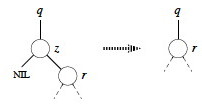

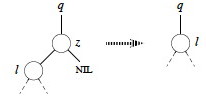

If z has no left child, replace z by its right child (which may or may not be NIL). This handles case 1 and half of case 2 in the conceptual breakdown above. (Lines 1-2 of final algorithm.)

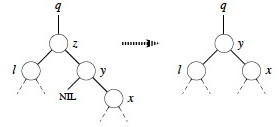

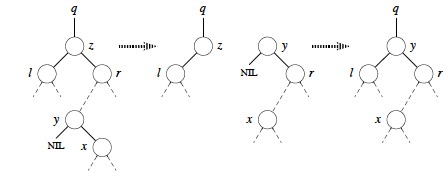

Now we just have to deal with the case where both children are present. Find z's successor (line 5), which must lie in z's right subtree and have no left child (why?). Handling depends on whether or not the successor is immediately referenced by z:

If successor y is z's right child (line 6), replace z by y, "pulling up" y's right subtree. The left subtree of y is empty so we can make z's former left subtree l be y's new left subtree. (Lines 10-12.)

Otherwise, y is within z's right subtree rooted at r but is not the root of this subtree (y≠r).

Now we are ready for the full algorithm:

The last three lines excecute whenever z has two children (the last two cases above).

Let's try TREE-DELETE(T,x) on x= I, G, K, and B:

Time: Everything is O(1) except for a call to TREE-MINIMUM, which is O(h), so TREE-DELETE is O(h) on a tree of height h.

The above algorithm fixes a problem with some published algorithms, including the first two editions of CLRS. Those versions copy data from one vertex to another to avoid a tree manipulation. If other program components maintain pointers to tree vertices (or their positions in Goodrich & Tamassia's approach), this could invalidate their pointers. The present version guarantees that a call to TREE-DELETE(T, z) deletes exactly and only vertex z.

You can probably find animations on the Web, but watch for the flaw discussed above.

We have been saying that the asympotic runtime of the various BST operations (except traversal) are all O(h), where h is the height of the tree. But h is usually hidden from the user of the ADT implementation and we are more concerned with the runtime as a function of n, our input size. So, what is h as a function of n?

The worst case is when the tree degenerates to a linear chain: h = O(n). This does not take advantage of the divide-and-conquer potential of trees.

Is this the expected case? Can we do anything to guarantee better performance? These two questions are addressed below.

The textbook has a proof in section 12.4 that the expected height of a randomly build binary search tree on n distinct keys is O(lg n).

We are not covering the proof (and you are not expected to know it), but I recommend reading it, as the proof elegantly combines many of the ideas we have been developing, including indicator random variables and recurrences. (They take a huge step at the end: can you figure out how the log of the last polynomial expression simplifies to O(lg n)?)

An alternative proof provided by Knuth (Art of Computer Programming Vol. III, 1973, p 247), and also summarized by Standish, is based on average path lengths in the tree. It shows that about 1.386 lg n comparisons are needed: the average tree is about 38.6% worse than the best possible tree in number of comparisons required for average search.

Surprisingly, analysts have not yet been able to get clear results when random deletions are also included.

Given the full set of keys in advance, it is possible to build an optimally balanced BST for those keys (guaranteed to be lg n height). See section 15.5 of the Cormen et al. text.

If we don't know the keys in advance, many clever methods exist to keep trees balanced, or balanced within a constant factor of optimal, by performing manipulations to re-balance after insertions (AVL trees, Red-Black Trees), or after all operations (in the case of splay trees). We cover Red-Black Trees in two weeks (Topic 11), after a diversion to heaps (which have tree-like structure) and sorting.

In Topic 09 we look at how a special kind of tree, a Heap, can be embedded in an array and used to implement a sorting algorithm and priority queues.

After a brief diversion to look at other sorting algorithms, we will return to other kinds of trees, in particular special kinds of binary search trees that are kept balanced to guarantee O(lg n) performance, in Topic 11.